Introduction

Most ideas that come to you in a dream should probably stay there. This one is probably in that category, but I decided to put in just enough work and thought to give it legs , grab a bit of attention ,and join us in the outskirts, so here goes.

Imagine a tailings impoundment that has undergone mineral reprocessing (via Regeneration?) through a multistage process involving minimal comminution, a two-stage flotation to reduce pyrite as much as possible, and maybe even a cleaner flotation to get a good separation between target metals and sulphides and inert tailings material. This inert tailings material likely looks very similar to the feed material before reprocessing, without some of the harmful potentially acid generating (PAG) sulphides and heavy metals. If thickened, dewatered, and screened, it might look a lot like a fine sand or clay. h9

Now imagine we take this material, supplement it with a few imported aggregates to ensure quality, set up a 3D concrete printer, and started printing pre-fabricated modern tiny homes for use in experiential hospitality and the growing housing shortage.

If you’re still in dreamland with me, great. Let’s keep going.

Mine Tailings- Importance of Mineralogy, Particle Size, and Geochemistry

Mineralogy, particle size, and geochemistry of the tailings are always going to be site-secific, but because the goal of tailings is to maximize gaunge material and minimize ore in the final stream, there are generally some consistent characteristics present across these categories. A study conducted in 2024 reviewed the literature for compositional properties of a wide range of tailings (Bragagnolo et al., 2024,) with a particular focus on mineralogy and particle size.

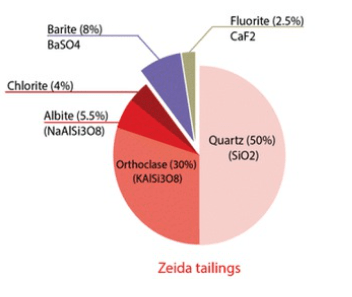

Typically, mine tailings contain a significant amount of quartz due to its general crustal abundance, often ranging from 30% to 60%. Clay minerals such as kaolinite, illite, and montmorillonite, can make up around 10% to 30% of the tailings. These clay minerals also bring the pozzolanic binding properties discussed later. Both plagioclase and potassium feldspar are commonly found, contributing about 5% to 20%. Carbonate minerals like calcite and dolomite can be present, usually around 5% to 15%. The typical villain in tailings, pyrite, chalcopyrite, and other sulfide minerals can be found in varying amounts, often between 1% to 10%. Oxides minerals can also be found. Hematite, magnetite, and other oxide minerals can also be present, typically around 1% to 5%.

These percentages have held true as I have begun reviewing tailings data for my work with Regeneration, but again, site specific values will reign in any given project application, especially as one as off the wall as tailings to concrete 3D-printed tiny homes.

Mine tailings generally exhibit a fine-grained particle size distribution relative to both the surrounding native fill or quaternary material, as well as to its host rock. This makes logical sense as most processing involves size reduction through grinding or milling. This more uniform size fragment helps better contain and control its impact on variability of reprocessing or reuse results, but can also introduce challenges.

Generally, the grinding and milling during comminution of the primary processing circuit leaves tailings with a maximum topsize of ~1mm. This topsize represents only a portion of the total material however, as the particle size grades on a curve down to ultrafine clay and silt sized particles. Additionally, the varied mineral phases of these particles dictate that their density and water absorption properties will also vary. A research paper published in 2019 reviewed a number of studies and found that the replacement of aggregates by tailings in concrete mixtures found decreased workability, decreased slump, increased density, and increased compressive strength (Gou et al., 2019.)

One of the primary studies reported in Gou et al., 2019 focused on the replacement of the fine aggregate portion of a concrete mix with tailings. Researchers utilized an M25 concrete mix, which calls for a cement: sand : coarse aggregate ratio of 1:1:2. The sand or fine aggregate portion is understood to represent particles less than ~10mm, while the coarse aggregate fraction will contain ~15-25mm particles (Thomas et al. 2013.)

With this in mind, only the largest particle size fragment in our tailings will provide sufficient aggregate material for a concrete mix, and will only supply the very finest fragment required by our mix. Thomas et al., 2013, concluded that no more than 30% tailings should be utilized in replacement of the fine aggregates portion of the mix. Additions greater than 30% resulted in poor curing times and reduced shear strength.

SCMs, Pozzolans, and Finding a Binder Replacement

The geochemical, mineralogical, and particle size characteristics of the tailings material are critical to understanding whether its use as a concrete substitute could be viable. Tailings are already used in industry as supplemental material in underground paste backfill. Though this is generally as an aggregate source and not as a binder. Specifically, the finer particle, clay-rich minerals in tailings could potentially be used as Supplementary Cementitious Materials (SCM), or pozollans to enhance concrete binding and strength or even replace traditional Portland cement binder. There has been significant progress in recent years in utilizing the fine clay particles in tailings as SCMs or pozzolans in mine operations or as a new salable product.

The startup company Envicore has steadily grown its technology and partnerships over the years. The company focuses on creating SCMs from tailings waste for use in ready mix concrete. The company was a featured startup in the Creative Destruction Lab startup incubator and recently signed a partnership with Heidelberg. Delivering this technology to industry will not only help reduce total tailings, but also impact the Portland cement market and rising binder costs. And Envicore isn’t the only player in this space. Many new startups are attempting to solve this problem and deliver reduced binder costs to the industry.

The Gou et al., 2019 review highlighted several studies that utilized the fine portions of tailings materials as SCMs. These substitutes were sourced from a variety of tailings types—molybdenum, iron ore, copper, t ungsten, and coal. (Jung et al., 2011, Zhou et al., 2017, Kim & Choi, 2016, Onuaguluchi &Eren 2012, Yague et al., 2018.) These experiments used site-specific tailings, a particle size and mineralogy analysis to determine the optimal activation method for pozzolanic and cementitious activity in the tailings materials. In the vast majority of cases, the recommended replacement of Portland cement by these materials maxed out at around 30%. Therefore, our experiment should not assume more than 30% replacement of traditional Portland cement, and we will need to import the remaining binder required for our mix design.

Easier Said than Done- Setting a Concrete Mix Design Criteria

Concrete is a mixture of water, a binding material, and a graded aggregate geologic material (such as sand and gravel). The ratio of these materials to one another makes up a concrete mix or ratio, and different ratios are utilized in different applications to achieve desired results in strength, durability, curing time, flow and placement. As mentioned above, there has been research into replacement of fine aggregates by tailings in concrete mixtures, often occurring in the finer size fragment. This is not ideal if we were to utilize an M25 or even M20 concrete mix as described in Thomas et al., 2013.

Lucky for us, 3D printed concrete nozzles ranging from 10mm-40mm for extrusion require us to adjust our mix a bit to reduce our reliance on the coarse aggregate fragment. In addition, these 3D printing technologies rely on a finer, more flowable concrete to deposit in layers. A study conducted by leading concrete 3D printing researchers Giuseppe Loporcaro and Don Clucas was presented at a 2022 concrete conference in New Zealand (Loparcaro & Clucas 2022.) Their study focused on reviewing concrete 3D printing mixes in the literature and testing their properties using a built, medium laboratory scale printer.

Interestingly, they determined that the optimal printable mix was a 3:2 sand:binder ratio. And the sand utilized was generally graded from 0.1mm to 1mm. This seems to be a fit for our tailings material at a high level. But of course as we have said throughout this exercise, site specific material characteristics will be the determining factor. I will be exploring more 3D printing mixes, their designs and experimental performance in the literature for future posts, but for now this assumptive mix can work for an idea exploration.

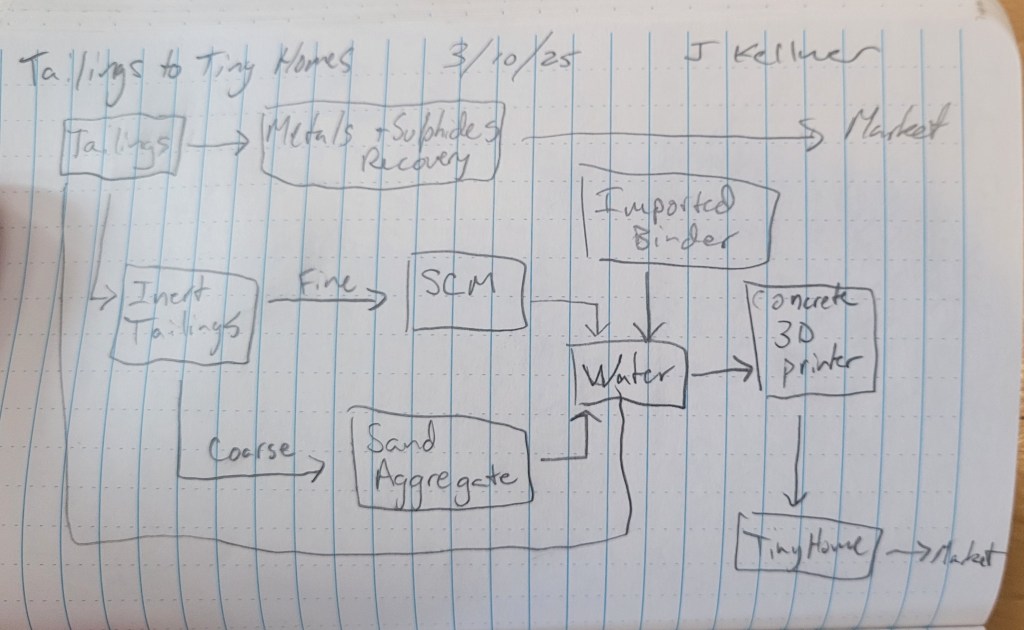

Potential Flow Sheet

Now comes the fun part. Provided our general technical assumptions can be applied in a site-specific setting, we can set up our concrete 3D printer to begin printing tiny homes. The market has seen the development of tiny homes explode as both a solution to growing housing shortages as well as a unique lodging option in the hospitality industry. In the latter, prefabricated designs have made their way onto resorts and outdoor experiential destinations, demonstrating a demand for consistency and scalability of the tiny house offering. With proper design for appeal and constructability, I see few reasons why the hospitality industry would not want to latch on to the good story of recycled, 3D printed lodgings. A deeper analysis into the demand of these products is warranted. But for now, the idea is set. Is it crazy enough to work?

Next Steps?

To further develop this concept, I will need to add in some analyses focused on the nitty gritty of engineering, importing of materials and actual product economics and demand. Some topics for future consideration include:

- Rough Mass Balance- Preliminary calculations for mass balance to determine what portion of material can act as SCM, aggregate sand etc.

- Geochemical/Mineralogical cutoffs- determining the ideal cutoffs/grades for geochemical composition in the tailings (ie. Quartz, feldspar, evaporite percentages)

- Potential upgrading/importing- quantities and characteristics of imported materials required to completment the tailings and achieve quality standards.

- Water requirements- estimation of water consumption in the 3D printing process

- Particle granulation or geopolymerization to solve the coarse aggregate problem?

- Financial Analysis- Determining how these assumptions would affect the financial viability of this idea.

Throughout this article we have explored and established some initial assumptions about the possibility of taking reprocessed mine tailings and utilizing them in a concrete 3D printing process to produce tiny homes for use in housing or hospitality. Thanks for exploring this idea with me. Feel free to drop me questions in the comments or on LinkedIn.

References

Bragagnolo, L., Prietto, P.D.M. & Korf, E.P. Compositional properties and geotechnical behavior of mining tailings: a review. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. (2024).

Gou, Mifeng, Zhou, Longfei and Then, Nathalene Wei Ying. “Utilization of tailings in cement and concrete: A review” Science and Engineering of Composite Materials, vol. 26, no. 1, 2019, pp. 449-464. https://doi.org/10.1515/secm-2019-0029

M.Y. Jung, Y.W. Choi, J.G. Jeong, Recycling of tailings from Korea Molybdenum Corporation as admixture for high-fluidity concrete, Environmental Geochemistry and Health 33 (2011) 113-119.

Y.J. Kim, Y.W. Choi, An experimental research on self-consolidating concrete using tungsten Mine Tailings, Ksce Journal of Civil Engineering 20(4) (2016) 1404-1410.

Giuseppe Loporcaro and Don Clucas , Mix Design and Fresh Properties of 3D Printed Concrete, Concrete NZ Conference 2022, October 13-15, 2022. https://cdn.ymaws.com/concretenz.org.nz/resource/resmgr/docs/conf/2022/s2b_p1.pdf

O. Onuaguluchi, O. Eren, Durability-related properties of mortar and concrete containing copper tailings as a cement replacement material, Magazine of Concrete Research 64(11) (2012) 1015-1023.

Thomas, B. S., Damare, A., & Gupta, R. C. (2013). Strength and durability characteristics of copper tailing concrete. Construction and Building Materials, 48, 894–900. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2013.07.075

Yagüe, S., Sánchez, I., Vigil de la Villa, R., García-Giménez, R., Zapardiel, A., & Frías, M. (2018). Coal-Mining Tailings as a Pozzolanic Material in Cements Industry. Minerals, 8(2), 46. https://doi.org/10.3390/min8020046

M.K. Zhou, Z.G. Zhu, B.X. Li, J.C. Liu, Volcanic Activity and Thermal Excitation of Rich-silicon Iron Ore Tailing in Concrete, Journal of Wuhan University of Technology-Materials Science Edition 32(2) (2017) 365-372.

Leave a comment